Ethiopian Demography and Health

The Ethiopian Somali is one of the least developed regions (even by Ethiopian standards) located in the east of the country. It has a along border with neighboring Somalia where Somalian ethnic Somalis live, and with Djibouti where Djibouti’s Somalis live. The region is remote with a mobile nomadic population and inadequate infrastructure. “This dismal situation could largely be attributed to traditional neglect of the region by the previous hostile regimes and past wars between Ethiopian and Somalia over the control of Ogaden.” [1] Climatically, it is mostly desert with high average temperatures and low bi-modal rainfall. Its economy is weak and reliant predominantly on traditional animal husbandry and marginal farming practices. It is also politically unstable:

Given the difficulty of imposing effective modern administration outside of the main urban centers, primary nomadic groups in the remote pastoral areas of the region rely upon traditional system of governance in which elders regulate lineage affairs [1]. The predominantly livestock-based economy has, for centuries, relied up on herding a primary stock of camels, flocks of sheep and goats, as well as the raising of cattle in settled agricultural areas where conditions are favorable [1]. "Export of live animals to the Gulf countries to the north is the main source of cash in the local economy. A secondary source of the regions cash flow is derived from agricultural goods (chat, coffee, fruits and vegetables) that are exported to Somalia and Djibouti” [1]

Two wars had been fought over ownership of this region between Somalia and Ethiopia – 1964 and 1977/78. The 1977/78 war between Ethiopia and Somalia led to the exodus of about 600,000 Ethiopian Somalis to Somalia. In addition the famine and “villagization” drive under the last government forced another 140,000 to join the ranks of those in refugee camps in 1984. With the involvement of donor agencies and governments, the refugee camps and the relief assistance delivered to them became part of the local economy.

A recent study of livelihood vulnerabilities in the Somali region which included a survey of 1100 Somali households has made numerous observations one of which reads as follows [2]:

“People in this region – pastoralists, agro-pastoralists, farmers and traders – have suffered a series of livelihood shocks in recent years, some natural (droughts, livestock disease), others political (a crackdown on contraband trade, bans by Gulf states on livestock imports, violent conflict between sub-clans or between Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) militia and the state). As a result of these multiple shocks, and because rainfall in the Horn of Africa has been low in recent years, questions are being asked about the sustainability of pastoralism as a livelihood system, not only in Somali Region but throughout the Greater Horn of Africa. The Government of Ethiopia, for instance, is advocating rural sedentarisation of pastoralists as one long-term option.”

Four dominant livelihood systems were identified in the region [2]:

1) Pastoralists engaged, primarily, in livestock rearing

Pastoralists engaged, primarily, in livestock rearing

2) Agro-pastoraliststs pursuing a mixed livelihood do livestock herding and crop farming

Agro-pastoraliststs pursuing a mixed livelihood do livestock herding and crop farming

3) Farmers leading a settled existence as producers of food crops for consumption as well as trade

Farmers leading a settled existence as producers of food crops for consumption as well as trade

4) Urban residents of small towns who earn a living through formal and informal employment

Urban residents of small towns who earn a living through formal and informal employment

The author cautions, however, that these would be deceptive classifications if viewed as distinct from each other with each group deriving sustenance from the land it occupies with no help at all from the others. Instead, the economic system is to be viewed holistically as “a complex interconnected system” in which a “… system of social networks and political negotiations, where the sustainability or vulnerability of each livelihood depends as much on the individual’s interpersonal relationships, and on international geopolitics, as on his or her assets and income at any point in time”. [2]

Farming in this Region is largely limited to the banks of the two permanent rivers – Dawa/Genale and Wabi Shebelle - running through the center and south of the region, as well a few Weredas in the north where rain-fed agricultures relies on seasonally occurring but unreliable rains. This suggests that significant challenges remain for settled agriculture in Somali as is evident in the following paragraph from the community study cited above:

“With no access to fertilizer, irrigation equipment, inputcredit or agricultural extension services, the prospects for farmers in Somali Region look unpromising. In this context, and with most available arable land already allocated and under cultivation, it is difficult to see how much more sedentarisation of Somali pastoralists along the banks of major rivers can be achieved.”

The study also identified four distinct water access systems [2]

1) Privately owned berkads (constructed water reservoirs)

Privately owned berkads (constructed water reservoirs)

2) Shallow wells to access ground water

Shallow wells to access ground water

3) The Shabelle and Dawa/Ganale, water systems, also shared with animals at the risk of

The Shabelle and Dawa/Ganale, water systems, also shared with animals at the risk of

contamination.

4) Piped water in major urban centers such as Jigjiga and Gode towns that benefit from a relatively

Piped water in major urban centers such as Jigjiga and Gode towns that benefit from a relatively

cheap and clean source of water throughout the year.

The region suffered a series of recent droughts and famines in 1999/2000 and in 2004 – described by some as the worst in recent memory - which led to numerous deaths both of humans and livestock. It also led to widespread poverty and displacement of many pastoralist families. Though it did not rise to the level of the “media famines” of the 1970s and 1980s, these rounds of draught and famine have also resulted in severe livelihood shocks. “Some observers believe that the current sequence of low rainfall years constitutes a permanent decline in rainfall, and some are even predicting the end of pastoralism in the Horn of Africa.” [2]. The region’s economic fortunes are also intertwined with and are affected by local, regional, and even international changes in economic circumstances which, for this region, are always changing, and in ways that are difficult to predict.

“The regional economy is closely linked to the economies of neighboring countries – Somalia, Somaliland, Djibouti, Kenya and the Gulf states – and any disruption to the flow of cash, livestock and commodities, either within Somali Region or between the region and the world beyond its borders, constitutes a major threat to many local livelihoods” [2]

International aid is helping make a difference. The United Nations and several NGOs have been operating in the region for years with the government’s permission which, at times, is difficult to secure due to ongoing civil conflicts [3]. Therefore, the backwardness of this region, even in comparison to many other regions in Ethiopia, and ongoing efforts to improve lives in the region should also be viewed “… against the backdrop of long-standing and recently intensified fighting between the Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF) and opposition armed fighters in the region.” [3]

Ongoing studies in the area are reporting on the gradual shifts in way of life away from nomadic herding toward settled agriculture. Moreover, a recent report has showed that this shift “…. is driven by multiple factors and results in a measured move away from the traditional nomadic pastoralist way of life towards a foundation of agro-pastoralist activities and sedentary farming” [3]. The jury is still out on the wisdom of such a transition given the finding that settled agriculturalists represented the group with the lowest income of the four economic groups listed above [2].

Climate and Land Use

The Somali region is mostly desert with high temperatures and low precipitation. Given the dominance of pastoralism, and the ongoing shift toward settled agriculture the dependence on rainfall is more obvious and stronger than in years past. “There are two primary rainy seasons throughout most of the region, the gu (long rainy season) from March to May, and the dayr (short rainy season) from October to December” [3]. A customary technique in water harvesting includes the collection of water in wells and storage containers to ensure the availability of supplies during the dry season. “But over the past two decades these rains have become increasingly unreliable; there were major droughts in 1984-85, 1994 and 1999-2000 (during which pastoralists claim to have lost 70-90 per cent of their cattle)” [3]. A creeping problem of environmental deterioration is linked to an emerging trend of widespread tree felling for conversion into charcoal. This is benefiting individuals involved in the trade but is clearly very detrimental to the community at large due to its destructive impacts on society in a region where resources are very scarce. [3]

Population Characteristics

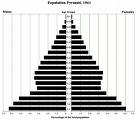

The Central Statistical Office (CSA) has estimated the 2008 (mid-year) population size in this region at 4,560,000 of whom 3,756,000 (82.4%) are rural residents [4]. The urban percentage of 17.6 is slightly higher than the national average. The population is almost entirely (95.6%) Somali and Moslem [3]. The Somali society “…is highly structured, anchored in the system of clans and sub-clans that bind and divide Somalis”. The systems forms the basis of much of “…the core social institutions and norms of traditional Somali society, including personal identity, rights of access to local resources, customary law (xeer), blood payment groups (diya), and support systems.” [3] . The region is divided into 9 zones and 53 Weredas.

“Hundreds of clans, sub-clans, sub-sub clans and so on exist and allegiances are complex. Fundamentally, the strongest allegiance is to the lowest clan division (i.e., allegiance to the subclan is stronger than allegiance to the clan), but this is a somewhat simplified depiction and it is important to accept that clan practices are “adaptable and dynamic, not static and timeless.” One sub-clan generally resides in one Kebele, meaning Weredas are home to multiple subclans, sometimes of the same overall clan, sometimes of different clans… At any particular time two sub-clans may be allies or adversaries and these relationships are constantly shifting in a process of fusion and fission between and among clan lineages” [3] With nearly four in five children living with both parents, the region also has the highest percentage of intact families. [5]

The educational level is low, and Islamic Koranic schools are more prevalent than modern secular schools. Many mention the consumption of khat as a pervasive social ill hampering learning and economic productivity. During the community study cited above a neighborhood leader in Gode characterized khat consumption as the greatest evil in the Somali society today as is the seemingly unrestricted flow of small arms in the region and across borders [3]. Nearly nine in ten females (the highest for any region in the country) and over four-fifths of males have no education. At 15.5 the region also has the lowest net attendance ratio at a primary school level (the percentage of primary school age children (7-12) who are actually going to a primary school. At 9.4, the ratio for secondary school attendance is the second lowest (after Afar).

Data on socioeconomic characteristics of the Somali gathered during the 2005 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) showed the Somali region to be by far the poorest.

Data on socioeconomic characteristics of the Somali gathered during the 2005 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) showed the Somali region to be by far the poorest (see graph below. It has the highest percentage of people in the lowest wealth quartile. It is obvious from the graph that the Somali and Afar regions are by far the poorest regions in Ethiopia. Nationally, a quarter of the population is in the lowest quartile wealth group. More than two thirds of Somalis and Afar are in this group. With more than 90 percent of Somali women and three-quarters of having no access at all to media sources of information, they are unlikely to benefit from information and national or international broadcasts on the benefits of education and the methods of wealth creation.

References;

1. http://www.africa.upenn.edu/EUE/ethsoml.html

http://www.africa.upenn.edu/EUE/ethsoml.html

2. Stephen Devereux. Vulnerable livelihoods in Somali Regions, Ethiopia. Institute of Development

Stephen Devereux. Vulnerable livelihoods in Somali Regions, Ethiopia. Institute of Development

Studies. Research Report 57. University of Sussex Brighton BN1 9RE UK. 2006.

3. CHF International. Grassroots Conflict Assessment of the Somali Region, Ethiopia. August

CHF International. Grassroots Conflict Assessment of the Somali Region, Ethiopia. August

2006.

4. Central Statistical Authority, Statistical Abstract. 2001 pp. 26-45

Central Statistical Authority, Statistical Abstract. 2001 pp. 26-45

5. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005 Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia ,

Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005 Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia ,

RC Macro, Calverton, Maryland, USA, September 2006

6. Central Statistical Authority, Statistical Abstract pp. 26-45

Central Statistical Authority, Statistical Abstract pp. 26-45

SOMALI

Population Distribution

The map below shows the population density in the Somali region based on the 2007 census. A possibly more accurate estimate (mid-2008) of the Wereda population is shown in the tables below [4]. With a population of over 300,000 Jijiga Wereda has the highest population and two other Weredas - Moyale and Awbere - have a population of over a quarter of a million. Gursum has the lowest population.

Source: [5]

Demographic Characteristics

The following table provides a brief glimpse into the socio-demographics characteristics of the Somali region featuring the the variables listed below. All of the numbers and summary results shown come from the 2005 DHS [5]

• Household and respondent characteristics

• Fertility levels and preferences

• Knowledge and use of family planning

• Childhood mortality

• Maternity care

• Childhood illness, treatment, and preventative actions

• Anaemia levels among women and children

• Breastfeeding practices

• Nutritional status of women and young children

Somali Wereda Map

If you would like to help update this page, please send comments and/or data (as an e-mail attachment) to Dr. Aynalem Adugna

at aynalemadugna@aol.com. Don't forget to indicate sources.